Riley detachable wheel 1987 article © Alan Teeder.

Written by Alan Teeder and published in installments in the Riley Register magazine in 1987 therefore some information i.e. telephone numbers, car owners etc. will be well out of date. For this page some reformatting to layout and addendum added. Reproduced with the kind permission of the author.

Introduction

Most Riley buffs have heard about the detachable wheels made by the Riley Cycle Company before the Great War, but will know very little about them. Apart from a picture in "Birmingham" and the patent abridgement reproduced in "As Old as the Industry" no details of their construction have been recently published. In this article I will describe the various patterns of Riley detachable wheels that were produced in the years 1907‑1914. The early history of the Riley companies is best covered in "Birmingham", or "The Riley Romance", if you are lucky enough to find a copy.

In researching this subject my sources of information have included all the known cars in the UK, the Riley car and detachable wheel catalogues, patent specifications and contemporary magazines. I would like to thank the car owners, both private and the museums, for allowing me to examine (and dismantle) their cars, as well as David Hales of the Veteran Car Club and the libraries at the Patent Office and Beaulieu who furnished me with large quantities of photocopied material. This article gives the information that I have been able to find, and I have deliberately refrained from making unsupported claims to bridge the many gaps that appeared.

The detachable wheel system has three important design features.

These are:

(i) A method of securing the inner hub to the outer hub.

(ii) A locking device to stop the securing mechanism from unlocking accidently.

(iii) A means of transferring braking and driving loads to the outer hub. This, in general, only applies to the rear wheels, since most cars of that period were not fitted with front brakes. Transmission brakes were common, and usually operated by the foot pedal. Rear wheel brakes would normally be attached to the inner hubs and worked by the brake lever.

The inner (or fixed) hub is the one that remains fixed to the car, to which it is attached by the axle bearings. The outer (or removable) hub forms the centre of the detachable wheel and carries the spokes.

The most detailed information source available is that in the various patent specifications. Inspection of the year books in the Patent Office library revealed no additions to the list of granted patents in Mike Plastow's bulletin article (no. 107) and David Styles' book.

To digress, the year books also list a similar number of Riley patents that were abandoned or declared void. This was particularly common in the years 1901 to 1910. The patent applications are listed in numerical order for each year together with an index of author's names.

Riley is not an uncommon name and this further complicates things. In particular one T. Riley had his name on three patent applications in 1910 which described wheel rims, cycle brakes and vehicle wheels. The other names on these applications included 'The Coventry Motor Wheel Co.' and 'The Coventry Garage and Wheel Co.'. I have not followed this up, but do not believe that there is any connection with "our" Riley family. Does anyone know?

The Patent Office library reading room in Chancery lane is open until 9 p.m. and they offer a while‑you‑wait photocopy service. It is cheaper to order by post from their sales branch (Tel Orpington 32111).

As far as is possible, I will refer to the wheels by their patent numbers.

Early Type. (Illustration 1)

The 1909 10 h.p. and 12/18 h.p. catalogue describes the earliest type of Riley detachable wheel that I have found. The same illustrations were included in an article in The Autocar for April 25 1908. It was not apparently covered by patent, and is probably the one which J.Pugh of Rudge Whitworth took exception to.

The 1907 9 h.p. catalogue says that detachable wheels are available as an option, but show no details. Riley detachable wheels were displayed at the November 1907 and 1908 Olympia shows.

The hub is not tapered and drive is transferred by means of a set of 6 driving pegs C on the inner hub A, which engage with holes E on the outer hub. Unless front wheel brakes were used, only one peg was usually fitted to the inner hub for the front wheels. The large nut H is screwed to a fine male thread F on the inner hub, and this secures the wheel. A ring of inwards facing ratchet teeth G are cut on the outside rim of the inner hub, and a spring loaded pawl K is pivoted in the nut itself. A lever L attached to the pawl extends out of one of the hexagon flats of the nut. When the full‑hexagon spanner is fitted, it depresses this lever thus releasing the pawl from the ratchet and allowing the nut to be undone. A final feature was a retaining ring screwed into the outside of the outer hub, which caused the wheel to be drawn off with the nut.

This is the only type of Riley wheel in which ratchet teeth are cut in the inner hub. The ratchets, when used, on the other wheels are all cut in the outer hub.

The other end of the spanner that Riley supplied was used as a tool for removing the engine valve caps.

This type of wheel is fitted to the following cars:

Type Year Chassis Registration Owner

12/18 1907 1374 T1915 R.M.Gilbert

12/18 1907 1478 NS105 Coventry Museum

12/18 ? 1798 ? David Styles

12/18 1908 1842 BY1963 Pam Knight

12/18 1910 ? ? Ivan Taylor (New Zealand)

Bob Gilbert says he doesn't think that his wheels have the ratchet device.

Since these wheels are fitted to so many 1907/1908 cars it seems fair to assume that they are the type referred to in the 1907 9 h.p. catalogue and the 1908/09 show reports.

1908 Improvements in or relating to Easily Detachable Road Wheels. (Percy Riley) (Illustration 2)

With the exception of the locking device on the 10 h.p. car at Syon Park, this patent bears no relation to any of the other designs. As with many of the patents two different constructions are shown. It is the only one with Percy's name against it.

The method of transferring the driving loads is unique in this design. A loose dog E mates with the half shaft (or a flange B that is fixed or splined to it), and with both the inner and outer hubs. The dog thus transfers driving forces from the half shaft directly to the detachable wheel.

The outer hub is secured by means of a nut K which screws onto the inner hub, and in the process holds dog E in position.

The security lock is formed by a disc M which has small projections engaging in corresponding recesses in the dog. A pin, on which the disc slides, prevents the locking disc from rotating relative to the nut. To release the locking device, the disc is pulled outwards against a light spring by means of a plunger L until it is clear of the dog. The nut may then be turned. The plunger would normally be operated by an attachment on the spanner.

The abridged patent specification is in "As Old as the Industry" (page 347). I have found no other mention of this type of detachable wheel. Was it ever produced?

Illustration 2 ‑ Patent 13,857/1908

1909 Syon Park Car (Illustration 3)

The car in Syon Park museum (i.e. the B.L. Heritage Collection) is a 10 h.p. 2 seat V‑twin. This is a very similar design to the 12/18 h.p. car. The only significant difference is the engine size. The hub shells are not tapered, but are otherwise of very similar shape to those used from patent 19,797/1910 onwards. (i.e. they look like those on my car.) They have three driving pegs to take the load.

Externally the nuts look like those described in the previous patent, with a central plunger to release a locking disc. The nut is held captive on the outer hub by a screwed ring, and works on a fine thread on the inner hub. The locking mechanism is released by pushing in the plunger until it clears the pin on which the locking disk slides. The ring has two projections which allow it to slide in slots on the threaded portion of the inner hub.

I believe that the wheels on a 9 h.p. car being restored in Yorkshire are also to this pattern.

Type Year Chassis Registration Owner

10h.p. 1909 2018 AB1390 Heritage Collection

9h.p. ? ? WS151 (Yorkshire)

1909 Syon Park Car (Illustration 3)

The car in Syon Park museum (i.e. the B.L. Heritage Collection) is a 10 h.p. 2 seat V‑twin. This is a very similar design to the 12/18 h.p. car. The only significant difference is the engine size. The hub shells are not tapered, but are otherwise of very similar shape to those used from patent 19,797/1910 onwards. (i.e. they look like those on my car.) They have three driving pegs to take the load.

Externally the nuts look like those described in the previous patent, with a central plunger to release a locking disc. The nut is held captive on the outer hub by a screwed ring, and works on a fine thread on the inner hub. The locking mechanism is released by pushing in the plunger until it clears the pin on which the locking disk slides. The ring has two projections which allow it to slide in slots on the threaded portion of the inner hub.

I believe that the wheels on a 9 h.p. car being restored in Yorkshire are also to this pattern.

Type Year Chassis Registration Owner

10h.p. 1909 2018 AB1390 Heritage Collection

9h.p. ? ? WS151 (Yorkshire)

1909 ‑ No. 2,297, Improvements in Hub Caps for Detachable Wheels. (The Riley Cycle Company, Limited and Victor Riley) (Illustrations 4, 5)

This patent only describes the means of securing the inner and outer hubs together. The patent does not describe how the drive loads are transferred.

The outer hub is secured to the inner hub by nut B, which screws onto the inner hub. To turn the nut, the spanner is fitted to the hexagon machined on outer cap A. The outer cap is loosely held to the nut, and to the outer hub, by a retaining ring C. Cut‑outs "a" in the cap engage with lugs "b" on the nut. The lugs are smaller than the cut‑outs, providing a degree of lost motion between nut and cap which is made use of by the locking mechanism. A slot "e‑e" is cut in the cap A, and within this slot is a spring loaded pawl "f" which is pivoted in the nut B. The pawl engages with ratchet teeth "l" cut on the inside of the outer hub. When the cap is turned anti‑clockwise by the spanner, the pawl is lifted when it strikes the end of the slot, and the ratchet is thus released. The lost motion is now fully taken up, and further rotation will undo the nut. Flange "q" on the nut pulls the outer hub off with the nut as it is undone.

The ratchet teeth, although of similar form to those in the "early" wheel, are cut in the outer hub.

In the 1911 10 and 12/18 h.p. catalogue a similar nut is shown in section. The main difference is that the thread on the inner hub, onto which nut B is screwed, is now female.

The catalogue drawing also shows that the drive is taken by means of projecting studs mounted on the inner hub. The hub is not tapered. The half shaft is fitted to the inner hub by a taper and key. The brake drum is fixed to the inner hub.

Riley advertising in 1910 also shows this form of wheel, complete with a two handled spanner. The spanner shows a feature mentioned in the catalogue, which prevents it from being removed unless the cap is in the locked position. When the cap is rotated anti‑clockwise from this position a projection on the rear of the spanner is trapped behind a flange on the ring C. When the cap is turned clockwise to tighten the nut the lost motion between them is first taken up before the nut begins to move. This allows the ratchet to engage and also brings the spanner projection in line with a cut‑out in the flange, thus allowing its removal.

"The Car Illustrated" of July 27 1910 devotes a whole page to this type of wheel.

There is every sign therefore that this wheel was produced. Unfortunately however, I have not seen it fitted to any existing Riley, but perhaps one still exists on another Edwardian car.

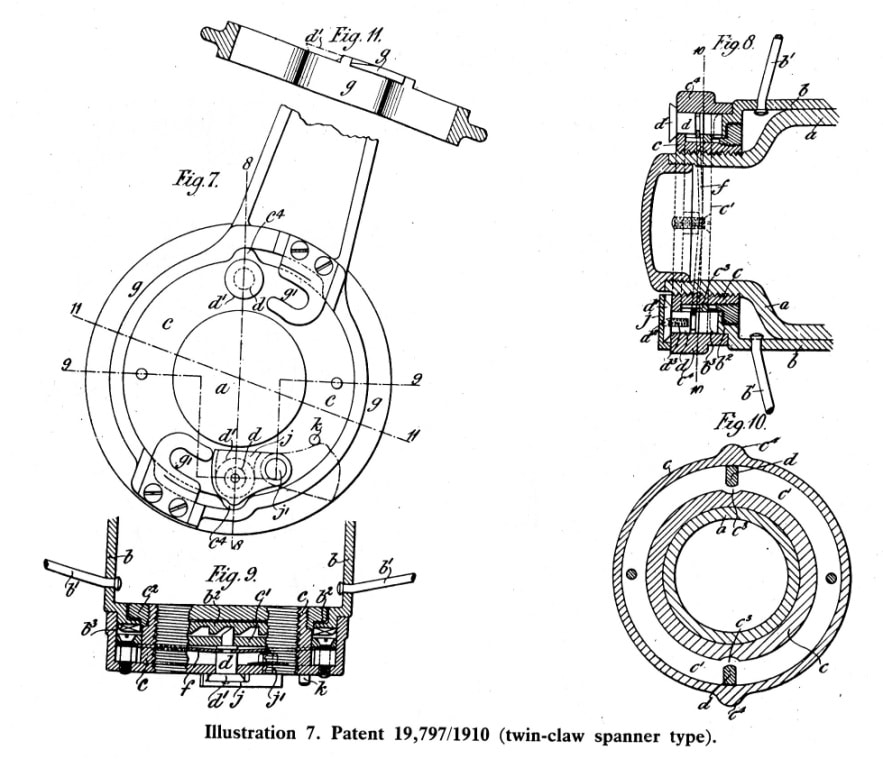

1910 ‑ No. 19,797, Improvements in Detachable Wheels for Vehicles, and in Spanners for Securing and Removing the same. (Victor Riley) (Illustrations 6‑8)

This patent describes the wheels fitted to my own car. I have also seen a set of these wheels fitted to a Deasey JDS. A rally report in the April 1985 New Zealand Riley Bulletin shows pictures of a 1908 Vauxhall which had apparently been so fitted in 1912.

The nut 'c' is of built‑up construction, and screws on to a coarse (8 t.p.i.) thread on the inner hub 'a'. All earlier Riley designs that I have seen seem to have had a fine thread. Drive is transmitted, as in the previous design, by pegs on the inner hub, which is again fixed to the half shafts by a taper and key.

This design introduces to Riley another design of locking device. A ring of ratchet teeth 'b3' are cut on the outside end face of the outer hub 'b'. A pair of sprung‑loaded pawls 'd' act on these teeth. The other ends of the pawls extend beyond the outer face of the nut, and are provided with flat head‑caps 'd1'. A special ring spanner 'g' is provided which fits over a pair of lugs 'c4' formed on the outside of the nut. The recesses into which the lugs fit are longer than the lugs, allowing lost motion between the spanner and nut.

To remove the wheel the spanner is turned anti‑clockwise. Claws 'g1' fitted to the spanner slide under the pawl‑caps, lifting them sufficiently to disengage from the ratchet teeth. Further rotation of the spanner then turns the nut as the lost motion is taken up. The nut is loosely held to the outer hub by a left‑ hand threaded retaining ring 'c2', which in turn also acts as a withdrawal collar pulling the outer hub off as the nut is unscrewed.

When the spanner is turned clockwise the claws slide out from under the pawl heads, thus allowing them to operate again. With further rotation the lost motion is taken up and the nut is tightened, to the accompaniment of a clicking sound from the ratchets. As a further safety feature, one of the pawl caps is provided with a hand‑operated swinging cover 'j'. When this cover is closed it covers the head of the pawl and prevents it from rising. In addition, when the cover is opened, it obstructs the removal and fitting of the spanner. This means that it is impossible to remove the spanner unless the cover is closed, which is in itself impossible unless the pawl is engaged in the bottom of a ratchet tooth.

This type of wheel is shown and described in the 1912 and 1913 10 h.p. and 12/18 h.p. catalogues. It is also shown, in a variety of sizes, in the 1912 detachable wheel catalogue, which lists 131 different makes of car to which Riley Detachable Wheels had been fitted. (This claim, by the way, was kept up to date in the press, and by late 1912 the total had risen to 180.) They were on display at the April and November 1911 and the March 1912 shows, but I do not know if the April show was their debut. The hub is tapered, and at the shows Riley were claiming that this feature took 90% of the drive, thus relieving the studs.

My experience with this design is that it provides a very quick and reliable means of changing wheels. No hammer is required although sometimes it is necessary to kick the spanner. The retaining ring always forces the wheel off. The swinging cover is a failure, since its pivot 'j1' rapidly wears and then does not prevent the pawl from disengaging. The cover is meant to be held closed by a small indentation which engages with a rounded projection 'b3' in the center of the pawl cap. In practice centrifugal (or centripetal for academics) force and vibration mean that the cover flies open as the car is driven. The pawls are still held in by their springs, and hopefully the wheel was tightened recently, so this is no real worry. Refurbishing the pivots only provided a temporary cure and soon they became as loose as before. Perhaps I should fit elastic bands or copper wire like they have on the wheel centers of Bugatti’s.

The patent also describes a variation in which the spring on one of the pawls is reversed and acts so as to disengage it from the ratchet. The swinging cover 'h' in this case is used to engage this pawl in one of the ratchet teeth against the action of the spring. Only one claw is now fitted to the spanner, which once again cannot be fitted or removed unless the cover is in the closed, safe, state. At Beaulieu last year (1986) I purchased such a single‑claw spanner, which indicates this variation was also produced.

The hexagonal brass hub nut which is visible in the center of the nut on my car is decorative (especially if polished), and retains the bearing grease. It is screwed into the inner hub.

Type Year Chassis Registration Owner

12/18 1911 2254 AF676 Alan Teeder

Deasey JDS 1910 EB485 N. Bradshaw

1908‑Vauxhall 1912 (New Zealand)

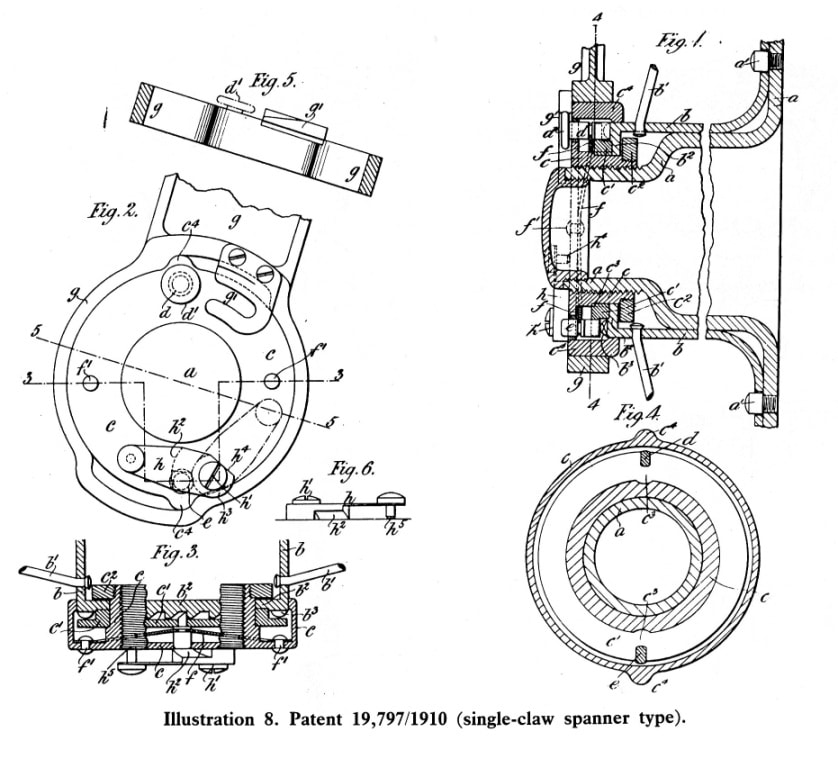

1912 ‑ No. 18,604, Improvements in Detachable Wheels and in Spanners for Fixing and Unfixing the same. (Victor Riley and Stanley Riley) (Illustrations 9‑11)

This specification is derived from the previous one. It only describes the nut and locking system.

Projections 26 on the inside of the ring spanner fit in grooves 23 in the outside of the nut to turn it. Two variations are shown for disengaging the pawls.

In the first arrangement the heads of the pawls 10 pass through slots 12 in a "claw plate" 9. These slots have inclines 14 machined in them. When the claw plate is rotated anticlockwise relative to the rest of the nut 1, the heads of the pawls are lifted by the inclines. Cut‑outs 24 on the outer edge of the claw plate engage with the projections 26 on the inside of the spanner. The cut‑outs 23 in the outside of the nut are longer than those in the claw plate so that the latter rotates and fully lifts the pawls before the spanner tries to undo the nut. A projection 27 at the back of the spanner catches behind the nut and prevents it from being removed from the nut when the claw plate is rotated into the lift position, in a similar manner to that described in the 1910 adverts (see 2,297/1909 patent above). A spring loaded ball 19 is forced into a detent 20 to retain the claw plate in the safe position.

For the second arrangement the heads of the pawls are brazed to a ring 30, which forms the outer cover of the nut assembly. Lifting ramps 32 on the spanner catch under lugs 33 lifting the whole ring when it is rotated anticlockwise. Otherwise all details are the same.

With both arrangements of this patent the safety covers in the previous 19,797/1910 design are dispensed with, complete reliance being placed on the springs.

Last year I acquired a pair of wheels to this second arrangement. In the patent drawings three sets of pawls are shown, but mine were only fitted with two.

This type of nut was new at the autumn 1912 motor show, together with the splined hub of patent No. 21,942/1912.

This specification is derived from the previous one. It only describes the nut and locking system.

Projections 26 on the inside of the ring spanner fit in grooves 23 in the outside of the nut to turn it. Two variations are shown for disengaging the pawls.

In the first arrangement the heads of the pawls 10 pass through slots 12 in a "claw plate" 9. These slots have inclines 14 machined in them. When the claw plate is rotated anticlockwise relative to the rest of the nut 1, the heads of the pawls are lifted by the inclines. Cut‑outs 24 on the outer edge of the claw plate engage with the projections 26 on the inside of the spanner. The cut‑outs 23 in the outside of the nut are longer than those in the claw plate so that the latter rotates and fully lifts the pawls before the spanner tries to undo the nut. A projection 27 at the back of the spanner catches behind the nut and prevents it from being removed from the nut when the claw plate is rotated into the lift position, in a similar manner to that described in the 1910 adverts (see 2,297/1909 patent above). A spring loaded ball 19 is forced into a detent 20 to retain the claw plate in the safe position.

For the second arrangement the heads of the pawls are brazed to a ring 30, which forms the outer cover of the nut assembly. Lifting ramps 32 on the spanner catch under lugs 33 lifting the whole ring when it is rotated anticlockwise. Otherwise all details are the same.

With both arrangements of this patent the safety covers in the previous 19,797/1910 design are dispensed with, complete reliance being placed on the springs.

Last year I acquired a pair of wheels to this second arrangement. In the patent drawings three sets of pawls are shown, but mine were only fitted with two.

This type of nut was new at the autumn 1912 motor show, together with the splined hub of patent No. 21,942/1912.

1912 ‑ No. 21,942, Improvements in or relating to Detachable Wheels. (Victor Riley and Stanley Riley) (Illustration 12)

This is a very short patent showing two main things.

The first is the abolition of the driving pegs which were used on all other known Riley Detachable wheels, except for the 1908 patent. They are replaced by splines. These are rather coarser than those on my Adelphi. The hub is tapered, which is meant to take the drive. The spline arrangement was available as an option, from autumn 1912.

The second part of the claim is a method of manufacturing the outer hub. The splines are formed by locally rolling the hub down to a smaller diameter, and then broaching. The ratchet ring is formed from a separate piece of metal from the rest of the hub, and is held in place by the outer set of spokes, which pass through it and the hub.

The two "spare" hubs that I have are made to this pattern. To use them on my car I have drilled a set of 6 holes for the driving pegs. The other dimensions are compatible and for a while I used one of the nuts with my spare wheel, which was nut‑less when found. This required the use of spacing rings to allow the pawls to operate. This was not completely successful as the addition of the spacers meant that insufficient threads engaged on the withdrawal ring 5. This made this wheel hard to remove, just like those on my Adelphi are sometimes when the splines bind. To machine the correct (19,797/1910) nut took a week of evenings, starting with a steel blank 5" diameter and 2 " long for the main part. Most of this was removed as swarf.

1912 ‑ No. 25,001, Improvements in or relating to Securing‑mechanism for Detachable Wheels. (Stanley Riley and Rapide Detachable Wheel Syndicate Limited) (Illustration 13)

This patent, on the face of it, looks like a development of the previous pair. If you read it however, it says "Patent of Addition to No. 12,264, 1910". This patent was not one of Riley's, but was granted to one Stephen Jamieson Ralph, an analytical chemist of Peterborough. The differences between the two designs are minimal. Mr. Ralph's patent is in turn an improvement on his own patent, No. 26,380/1909.

The pawls F are brazed to the outer cover H of the nut. However to release the pawls the cover is pulled outwards by hand. Inside the body E of the nut is a spring loaded latch K which holds the cover in this position until the latch is released. The clever bit is that the latch is released automatically when the nut is unscrewed.

A smooth ring D4 is machined in the middle of the ratchet teeth D. A plunger I is pressed into this by a light spring I1. As the nut is unscrewed, it lifts away from the outer hub A (but not too far because of the withdrawal ring E6 which holds the nut to the outer hub). The plunger thus extends further. When the nut is clear of the ratchet ring, the plunger releases the latch. The pawls are now released and will do their job when the wheel is next tightened.

A ring spanner with projections E9 engaging in grooves E8 on the nut is used, as in the previous specifications.

This description relates equally to both the Riley (25,001/1912) and Ralph (12,264/1910) patents. In view of the similarities of the rest of the specification to Riley patents 19,797/1910 and 18,604/1912 and Ralph's patent 26,380/1909 I think that there is a small mystery to clear up.

I have never seen any wheels or other references to this specification.

1912 Motor Show

Riley introduced hubs to patents No. 18,604/1912 and No. 21,942/1912. A wheel, hub and spanner to this pattern is shown on page 33 or 44 of Birmingham depending on which edition you have. Also made available as an option for Riley wheels were "Q.D." detachable rims by the Goodyear Tyre Co. of America. Various makes of detachable rims were very popular at that time, since they made the removal of tyres much simpler. A fixed wire wheel for light cars was also shown.

1913 Motor Show (Illustration 14)

New detachable wire wheels for light cars and a special one for Ford cars were on show. Both were of the now familiar "bolt‑on" type. These were either 3, 4 or 6 stud as appropriate. The 6 stud wheels used 3 plain drive studs and 3 threaded studs to secure the wheel.

The wheels were exhibited at overseas motor shows. There are reports of the Brussels and Russian shows.

Riley detachable wheel for Ford cars

A special type of Riley wheel has been introduced by Riley (Coventry), Limited, to form a cheap detachable and interchangeable wire wheel for Ford cars which can be fitted in about an hour by any Ford dealer. The device was bought

specially to our notice by Messrs. Albert E. Oakley and Co., of 38, Broad Street, W., who holds the agency for the southern counties, and from the accompanying illustration of a back hub wheel it will be seen by those familiar with Ford practice to consist of a very simple transformation. “A” is the existing wood wheel flange and brake drum left in situ on the axle even to the hub cap. The remainder of the standard wheel is entirely removed. In the six holes left by the bolts in the flange “A” are bolted permanently three coned pins and three bolts arranged alternately and shown in detail in the drawing. The collars on these pins take the drive. And the nuts on the three screwed bolts hold the new wire wheel to the existing flange, the hub of the detachable wheel passing over the permanent hub without disturbing it in any way whatsoever. A brace with a box spanner end passed between the wire spokes easily reaches and screws up or unscrews the nuts “B”.

Riley introduced hubs to patents No. 18,604/1912 and No. 21,942/1912. A wheel, hub and spanner to this pattern is shown on page 33 or 44 of Birmingham depending on which edition you have. Also made available as an option for Riley wheels were "Q.D." detachable rims by the Goodyear Tyre Co. of America. Various makes of detachable rims were very popular at that time, since they made the removal of tyres much simpler. A fixed wire wheel for light cars was also shown.

1913 Motor Show (Illustration 14)

New detachable wire wheels for light cars and a special one for Ford cars were on show. Both were of the now familiar "bolt‑on" type. These were either 3, 4 or 6 stud as appropriate. The 6 stud wheels used 3 plain drive studs and 3 threaded studs to secure the wheel.

The wheels were exhibited at overseas motor shows. There are reports of the Brussels and Russian shows.

Riley detachable wheel for Ford cars

A special type of Riley wheel has been introduced by Riley (Coventry), Limited, to form a cheap detachable and interchangeable wire wheel for Ford cars which can be fitted in about an hour by any Ford dealer. The device was bought

specially to our notice by Messrs. Albert E. Oakley and Co., of 38, Broad Street, W., who holds the agency for the southern counties, and from the accompanying illustration of a back hub wheel it will be seen by those familiar with Ford practice to consist of a very simple transformation. “A” is the existing wood wheel flange and brake drum left in situ on the axle even to the hub cap. The remainder of the standard wheel is entirely removed. In the six holes left by the bolts in the flange “A” are bolted permanently three coned pins and three bolts arranged alternately and shown in detail in the drawing. The collars on these pins take the drive. And the nuts on the three screwed bolts hold the new wire wheel to the existing flange, the hub of the detachable wheel passing over the permanent hub without disturbing it in any way whatsoever. A brace with a box spanner end passed between the wire spokes easily reaches and screws up or unscrews the nuts “B”.

Illustration 14 – Drawing and legend of the Riley detachable wheel for Ford's.

Non‑Detachable Wheels

To complete my list of early cars, the following are not fitted with detachable wheels. To remove these wheels it is necessary to dismantle the cup and cone type bearings.

Type Year Chassis Registration Owner

9 h.p. 1907 1058 508WAR (AR3) J.N.McLaren

9 h.p ? ? ? R.Forsey

9 h.p 1907 1112 YU4031 B.L. Heritage

I think it unlikely that any tricars were fitted with detachable wheels. Tricar production effectively ceased at about the same time as the detachable wheels were introduced. Detachable wheels would not be suitable for the rear wheel in any case.

Competition

From the beginning the Riley Company was keen to be seen in competition. Victor Riley in particular was a frequent competitor in hill climbs. All the car catalogues list the success that Riley’s met with.

In 1908 the French were busy adapting the rules of Grand Prix racing, and had banned detachable wheels (but not detachable rims), resulting in Napier withdrawing from that year's event. Victor Riley wrote to The Autocar “... speed contests such as the Grand Prix should be intended to 'improve the breed' of automobiles generally, and it would appear therefore, that detachable wheels should be welcomed, their advantage to the tourist being obvious."

For the 1911 light car Grand Prix race at Boulogne two of the entrants were on Riley detachable wheels. The highest placed of these was a Gregoire which came 5th. A similarly fitted Gregoire came first in the 1913 Coupe de la Sarthe. Riley made sure that references to these results appeared in the press.

Readers of "Birmingham" will know that the Blitzen Benz was fitted with special Riley wheels.

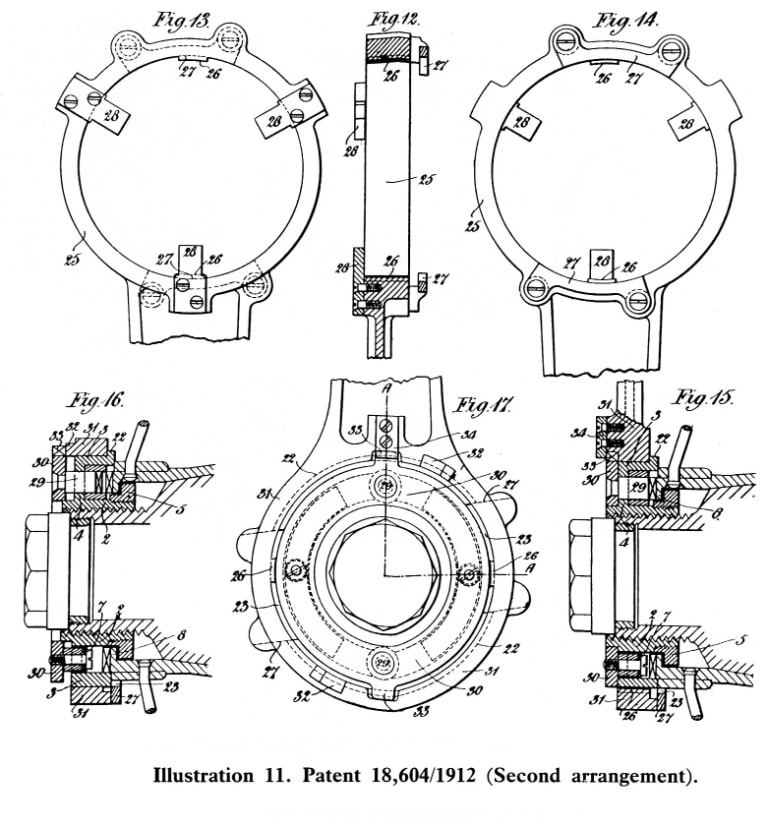

Other Manufacturers (Illustrations 15, 16)

The market leader was the Rudge Whitworth Company. They were much more aggressive than Riley, who relied upon weekly adverts in the press and customer goodwill. Other makes included Dunlop, Sankey, Newton and Bennett, Goodyear, Harris, together with car makers such as Austin, Talbot, Rover, Vulcan, Humber, Sunbeam, Mass, Hampton making their own from time to time.

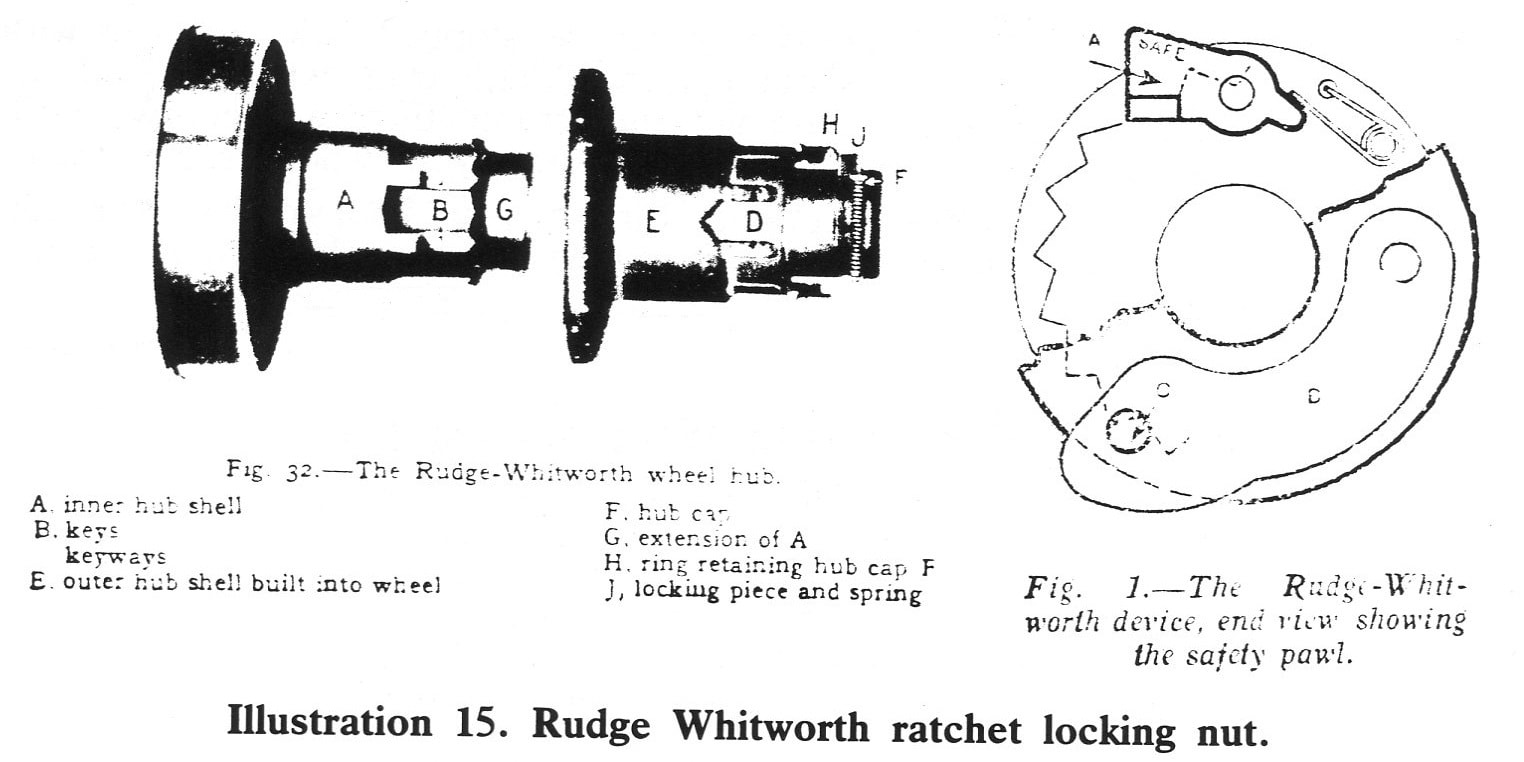

Early Rudge Whitworth wheels transmitted drive by large slots cut into the inner and outer hubs. A ratchet pawl was released by the spanner when it was required to remove the wheel. Later on a splined drive was introduced, and a dead lock pin inserted into the ratchet as a safety device (Illustration 15).

The ratchet was superseded in 1913 by the Rudge Whitworth coned locking device that most Riley owners are familiar with (See Illustration 16). The parallel splines are a loose fit on the inner hub and a proportion of the car's weight is carried by the nut itself. The nut tightens on the male coned surface of the end of the outer hub, and has a mating female cone machined in it. If the nut is loose there will be a gap between these two cones, allowing the wheel to wobble slightly. The car weight will now be carried at a single line of contact between the coned surfaces of nut and wheel. As there is a gap between the cones, the effective diameter of the cone on the hub is smaller than that of the nut.

The line of contact therefore rolls relative to hub and nut as the car moves. This, the theory says, can be likened to an epicyclic gear. Riley owners are well known for their understanding of this work of the devil and will immediately deduce that in this arrangement, with the planet gear (i.e. the outer hub) rotating, and the planet carrier fixed (i.e. in this case always vertical), the outer gear (i.e. the nut) will tend to rotate backwards. By placing left hand threads on one side of the car, and right hand threads on the other, this tendency is used to tighten up the nut. The weight is also carried by the threads at the bottom of the nut, and the relative motion between the nut and the inner hub induced at this point is in the same direction, and also adds to the tightening action. Once the nut has tightened, the clearance between the cones is taken up and the rolling action stops.

So confident were Rudge Whitworth of this theory that one of their patents describes a nut in which ball bearings are added to enable it to tighten itself more easily. It was only necessary to fit the nut hand tight, and after 1/2 mile or so (forward please!) it would require a spanner to release it. I don't believe theories like this so I always knock my Adelphi's wheel nuts up tight, especially on the wheels with dodgy splines.

The early Rudge tapered‑cone wheel nuts were circular, and were removed with a special spanner. The knock‑on ears did not appear until much later.

Non‑Detachable Wheels

To complete my list of early cars, the following are not fitted with detachable wheels. To remove these wheels it is necessary to dismantle the cup and cone type bearings.

Type Year Chassis Registration Owner

9 h.p. 1907 1058 508WAR (AR3) J.N.McLaren

9 h.p ? ? ? R.Forsey

9 h.p 1907 1112 YU4031 B.L. Heritage

I think it unlikely that any tricars were fitted with detachable wheels. Tricar production effectively ceased at about the same time as the detachable wheels were introduced. Detachable wheels would not be suitable for the rear wheel in any case.

Competition

From the beginning the Riley Company was keen to be seen in competition. Victor Riley in particular was a frequent competitor in hill climbs. All the car catalogues list the success that Riley’s met with.

In 1908 the French were busy adapting the rules of Grand Prix racing, and had banned detachable wheels (but not detachable rims), resulting in Napier withdrawing from that year's event. Victor Riley wrote to The Autocar “... speed contests such as the Grand Prix should be intended to 'improve the breed' of automobiles generally, and it would appear therefore, that detachable wheels should be welcomed, their advantage to the tourist being obvious."

For the 1911 light car Grand Prix race at Boulogne two of the entrants were on Riley detachable wheels. The highest placed of these was a Gregoire which came 5th. A similarly fitted Gregoire came first in the 1913 Coupe de la Sarthe. Riley made sure that references to these results appeared in the press.

Readers of "Birmingham" will know that the Blitzen Benz was fitted with special Riley wheels.

Other Manufacturers (Illustrations 15, 16)

The market leader was the Rudge Whitworth Company. They were much more aggressive than Riley, who relied upon weekly adverts in the press and customer goodwill. Other makes included Dunlop, Sankey, Newton and Bennett, Goodyear, Harris, together with car makers such as Austin, Talbot, Rover, Vulcan, Humber, Sunbeam, Mass, Hampton making their own from time to time.

Early Rudge Whitworth wheels transmitted drive by large slots cut into the inner and outer hubs. A ratchet pawl was released by the spanner when it was required to remove the wheel. Later on a splined drive was introduced, and a dead lock pin inserted into the ratchet as a safety device (Illustration 15).

The ratchet was superseded in 1913 by the Rudge Whitworth coned locking device that most Riley owners are familiar with (See Illustration 16). The parallel splines are a loose fit on the inner hub and a proportion of the car's weight is carried by the nut itself. The nut tightens on the male coned surface of the end of the outer hub, and has a mating female cone machined in it. If the nut is loose there will be a gap between these two cones, allowing the wheel to wobble slightly. The car weight will now be carried at a single line of contact between the coned surfaces of nut and wheel. As there is a gap between the cones, the effective diameter of the cone on the hub is smaller than that of the nut.

The line of contact therefore rolls relative to hub and nut as the car moves. This, the theory says, can be likened to an epicyclic gear. Riley owners are well known for their understanding of this work of the devil and will immediately deduce that in this arrangement, with the planet gear (i.e. the outer hub) rotating, and the planet carrier fixed (i.e. in this case always vertical), the outer gear (i.e. the nut) will tend to rotate backwards. By placing left hand threads on one side of the car, and right hand threads on the other, this tendency is used to tighten up the nut. The weight is also carried by the threads at the bottom of the nut, and the relative motion between the nut and the inner hub induced at this point is in the same direction, and also adds to the tightening action. Once the nut has tightened, the clearance between the cones is taken up and the rolling action stops.

So confident were Rudge Whitworth of this theory that one of their patents describes a nut in which ball bearings are added to enable it to tighten itself more easily. It was only necessary to fit the nut hand tight, and after 1/2 mile or so (forward please!) it would require a spanner to release it. I don't believe theories like this so I always knock my Adelphi's wheel nuts up tight, especially on the wheels with dodgy splines.

The early Rudge tapered‑cone wheel nuts were circular, and were removed with a special spanner. The knock‑on ears did not appear until much later.

The other makes of detachable wheel displayed every possible type of ratchet or locking pin that could be imagined. Identification is difficult, since if a name was embossed on a wheel center then it was usually that of the car manufacturer. Rudge are an exception to this and many of their wheel nuts are marked. I have only seen the Riley name embossed on the "early" type nut fixed to their own 12/18 h.p. cars. The nuts on my own car carry no identification, even internally.

Riley wheels were also produced under license in Paris.

Litigation

The reasons for this were that the designs could be patented or registered. This meant that you had to pay royalties to use the other firm's design. One or two cases went to court, and were reported in the automobile press of the time. Napier claimed from time to time that they held a master patent on all detachable wheels. They usually lost with that one.

I have found reports of two cases in the motoring press between J. Pugh of the Rudge Whitworth Company and Riley. In January 1912 Pugh lost when he claimed that Riley had infringed his registered design on triple spoking of wire wheels. Riley had however arranged their third row to cone in the opposite direction to Pugh, and this was good enough to get away with it.

The second case was incomprehensible to all save lawyers. Once again J. Pugh challenged Riley, who joined with the British Gregoire Agency and the Goodyear Motor Wheel Company of Dudley. Pugh won the first round, which lasted 3 days in 1911. Riley were ordered to destroy the offending articles and pay Pugh's costs. I think that this includes compensation for loss of earnings. Riley claimed that the patent was not valid, and that Pugh, Arrol Johnston and Napier had anticipated its claims.

In 1912 this case reached the appeal court. All three judges said the patent was valid, but disagreed on engineering details. The Master of the Rolls said that the Riley design did not indicate when the hub was fully home, that their grease cap was not part of the hub, and the inner hub did not pass fully through the outer hub and locking ring. In his opinion it did not infringe the patent. The other two judges disagreed and gave a point’s win to Pugh.

The last round, in 1914 again lasted 3 days. The Lord Chancellor said that Pugh's design was made from a combination of well-known engineering components, and that he had patented a particular combination of them. Riley had used a different blend of the same, and other, bits, and this was sufficiently different to not infringe the patent. Final judgement was given in favour of Riley, with costs.

By this time Rudge Whitworth had stopped making wheels with ratchet locks, but this did not stop Pugh from writing to all the motoring magazines reminding manufacturers that his patents were still valid, and that he would continue to sue anyone who infringed them.

The "Riley Romance" and "Birmingham" both say that one action was still outstanding at the start of the Great War, but give no further details.

Conclusions

In 1912 the Riley Cycle Company decided to stop car production, and concentrate on wheels. The Riley brothers combined their interests to form the Riley Motor Manufacturing Company at a new works and thus kept the car in production. It is all the more surprising then that after the Great War the wheel business was quietly dropped, and the production of cars alone were slowly resumed. Initial production would have been of the 1913 17 h.p. 3 litre cars, using up the pre‑war stocks. Possibly this is how the last sets of wheels were used up, but none of these 4 cylinder cars seem to have survived.

Much care is needed when interpreting the evidence now available. For example, a survey of detachable wheels in "The Motor" for January 1914 gives a description of the 1910 patent wheel, and even describes it as Riley's latest type!

The wheel type is not a completely reliable way of dating a car. In 1912 Riley advertised that they would, for a small cost, replace early detachable wheels with their latest type. Many cars, such as the 1908 Vauxhall in New Zealand, were fitted with detachable wheels after some years use.

From the above it can be seen that Riley produced a large range of different wheel designs in a very short period. Was this an omen foretelling the range of cars which appeared in the next 20 years?

If any members have queries, additional information, or corrections I would be very pleased to hear from them.

Postscript, (Illustration 17)

This short article continues the story of Riley wheel manufacture in the immediate post‑war period.

In June 1918, some 5 months before the end of the first war, Riley were announcing to the press that they had been developing a new light car chassis over the past 3 or four years. This announcement was repeated nearly a year later, with a photograph of a 17hp car wearing Riley disc wheels. (Illustration 17). In the Autocar this picture was labeled "A forerunner of the 1919 Riley Car". The car has the pre‑war 5 seat torpedo body, and retains the characteristic round radiator. No details of the hub or wheel fixing are obvious from the picture. Perhaps it had received the attentions of an artist.

The 11 h.p. sidevalve Riley seems to have finally appeared in the autumn of 1919 and was shown at Olympia. This car featured extensive use of pressed steel parts, including these same disc wheels.

At this point it is interesting to note that in the Autocar report of the Olympia show it was recorded that Riley were producing detachable wire wheels for Ford and light cars.

The Riley (Coventry) company, with Harry Rush, were granted two patents in 1919 relating to disc wheels.

Riley wheels were also produced under license in Paris.

Litigation

The reasons for this were that the designs could be patented or registered. This meant that you had to pay royalties to use the other firm's design. One or two cases went to court, and were reported in the automobile press of the time. Napier claimed from time to time that they held a master patent on all detachable wheels. They usually lost with that one.

I have found reports of two cases in the motoring press between J. Pugh of the Rudge Whitworth Company and Riley. In January 1912 Pugh lost when he claimed that Riley had infringed his registered design on triple spoking of wire wheels. Riley had however arranged their third row to cone in the opposite direction to Pugh, and this was good enough to get away with it.

The second case was incomprehensible to all save lawyers. Once again J. Pugh challenged Riley, who joined with the British Gregoire Agency and the Goodyear Motor Wheel Company of Dudley. Pugh won the first round, which lasted 3 days in 1911. Riley were ordered to destroy the offending articles and pay Pugh's costs. I think that this includes compensation for loss of earnings. Riley claimed that the patent was not valid, and that Pugh, Arrol Johnston and Napier had anticipated its claims.

In 1912 this case reached the appeal court. All three judges said the patent was valid, but disagreed on engineering details. The Master of the Rolls said that the Riley design did not indicate when the hub was fully home, that their grease cap was not part of the hub, and the inner hub did not pass fully through the outer hub and locking ring. In his opinion it did not infringe the patent. The other two judges disagreed and gave a point’s win to Pugh.

The last round, in 1914 again lasted 3 days. The Lord Chancellor said that Pugh's design was made from a combination of well-known engineering components, and that he had patented a particular combination of them. Riley had used a different blend of the same, and other, bits, and this was sufficiently different to not infringe the patent. Final judgement was given in favour of Riley, with costs.

By this time Rudge Whitworth had stopped making wheels with ratchet locks, but this did not stop Pugh from writing to all the motoring magazines reminding manufacturers that his patents were still valid, and that he would continue to sue anyone who infringed them.

The "Riley Romance" and "Birmingham" both say that one action was still outstanding at the start of the Great War, but give no further details.

Conclusions

In 1912 the Riley Cycle Company decided to stop car production, and concentrate on wheels. The Riley brothers combined their interests to form the Riley Motor Manufacturing Company at a new works and thus kept the car in production. It is all the more surprising then that after the Great War the wheel business was quietly dropped, and the production of cars alone were slowly resumed. Initial production would have been of the 1913 17 h.p. 3 litre cars, using up the pre‑war stocks. Possibly this is how the last sets of wheels were used up, but none of these 4 cylinder cars seem to have survived.

Much care is needed when interpreting the evidence now available. For example, a survey of detachable wheels in "The Motor" for January 1914 gives a description of the 1910 patent wheel, and even describes it as Riley's latest type!

The wheel type is not a completely reliable way of dating a car. In 1912 Riley advertised that they would, for a small cost, replace early detachable wheels with their latest type. Many cars, such as the 1908 Vauxhall in New Zealand, were fitted with detachable wheels after some years use.

From the above it can be seen that Riley produced a large range of different wheel designs in a very short period. Was this an omen foretelling the range of cars which appeared in the next 20 years?

If any members have queries, additional information, or corrections I would be very pleased to hear from them.

Postscript, (Illustration 17)

This short article continues the story of Riley wheel manufacture in the immediate post‑war period.

In June 1918, some 5 months before the end of the first war, Riley were announcing to the press that they had been developing a new light car chassis over the past 3 or four years. This announcement was repeated nearly a year later, with a photograph of a 17hp car wearing Riley disc wheels. (Illustration 17). In the Autocar this picture was labeled "A forerunner of the 1919 Riley Car". The car has the pre‑war 5 seat torpedo body, and retains the characteristic round radiator. No details of the hub or wheel fixing are obvious from the picture. Perhaps it had received the attentions of an artist.

The 11 h.p. sidevalve Riley seems to have finally appeared in the autumn of 1919 and was shown at Olympia. This car featured extensive use of pressed steel parts, including these same disc wheels.

At this point it is interesting to note that in the Autocar report of the Olympia show it was recorded that Riley were producing detachable wire wheels for Ford and light cars.

The Riley (Coventry) company, with Harry Rush, were granted two patents in 1919 relating to disc wheels.

1919 (April) No. 150795, Improvements in Wheels for Vehicles (Riley (Coventry) Ltd, H. Rush) (Illustration 18)

Riley's disc wheel was made from a series of dished steel discs which were riveted or welded together. The number and size of the discs could be varied to produce wheels of various strengths and stiffnesses. This construction was claimed to damp out vibrations, an effect which could be further enhanced by interposing thin discs of suitable sound deadening material. One of the discs could also form the hub cap, and the wheel could be attached to the hub either by "the usual ring of bolts or by a centrally placed locking and withdrawing device".

The rim was attached to the main disc by welding, or alternatively could be constructed as a split‑rim, thus allowing simpler tyre removal. These two arrangements, together with a variation on the hub design are shown in illustration 18.

Riley's disc wheel was made from a series of dished steel discs which were riveted or welded together. The number and size of the discs could be varied to produce wheels of various strengths and stiffnesses. This construction was claimed to damp out vibrations, an effect which could be further enhanced by interposing thin discs of suitable sound deadening material. One of the discs could also form the hub cap, and the wheel could be attached to the hub either by "the usual ring of bolts or by a centrally placed locking and withdrawing device".

The rim was attached to the main disc by welding, or alternatively could be constructed as a split‑rim, thus allowing simpler tyre removal. These two arrangements, together with a variation on the hub design are shown in illustration 18.

1919 (June) No. 150795, Improvements in Wheels for Vehicles (Riley (Coventry) Ltd, H. Rush) (Illustration 19)

In this development of the laminated wheel, the laminations are spaced by rings so as to provide bracing. Three versions of the construction are shown in illustration 19.

In this development of the laminated wheel, the laminations are spaced by rings so as to provide bracing. Three versions of the construction are shown in illustration 19.

Wheels, (Illustrations 20, 21)

Disc wheels were fitted to the side valve cars up until at least 1924, by which time wire wheels were supplied on de‑luxe and sporting models.

I have only seen one car with Riley Disc wheels. This is the 1922 2 seat side valve coupe owned by Jim Hennequin, the boss of our spares organization. These are built from 3 discs, which are riveted to a hub cap. They are secured to the hub by a ring of 6 bolts. Illustration 20 shows a front wheel from this car.

Other manufacturers, including Dunlop, were also producing disc wheels. An Autocar survey found that 27% of cars were built with disc wheels in 1923. The Riley system, combining both laminated construction and a dished section allowed wheels with the necessary lateral strength to be produced from quite thin steel sheet. The weight was comparable to that of the wire wheels. A further advantage of the dished section was that the front axle swivel (king) pins could point directly at the tyre, without resorting to wheel camber or king pin inclination to keep the steering loads light. See Illustration 21.

Riley's side valve car wheels, like all Riley products before them had done, and those after were to continue to do, came in many variations. From 1923 the catalogue illustrations depict only 4 studs on the disc wheels. In 1924 the hub seems to be reinforced. The catalogue pictures are reproduced in "As Old as the Industry", together with cross sectional drawings of various parts of the car including the wheels.

From 1924 onwards Riley side valve cars were available with artillery pattern or wire wheels. The stud pattern continued to fluctuate. Perhaps one of the side‑valve experts could sort it out.

List of cars fitted with Riley wheels, (Illustration 22)

I will conclude by returning to the pre first war period, Illustration 22 is the list of cars given in the 1912 Riley Detachable Wire Wheels Catalogue. Please note that inclusion in this list does not mean that Riley Wheels were used as standard, it only claims that a car of that make has been so fitted.

Footnote on the published list of cars using Riley wheels

The following is a little comment from David Styles on the published list of cars which used Riley wheels.

In that list there are some worthy tales to tell – of the 100hp Austin’s developed for the 1908 French Grand Prix, where the cars were banned from carrying spare wheels because competitors were not allowed to carry “spare parts”. The mighty Blitzen Benz cars were fitted with special wheels made by Riley and Victor Hemery set up a new speed record at Brooklands in 1909 of 127.4 mph. In America, the famous Barney Oldfield broke that record with 131.1 mph speed at Daytona Beach and in 1911, another American, Bob Burman then set a new world speed record of 141.7 mph, which stood until after the Great War.

Dr. Ferdinand Porsche (father of the present Dr. Ferry Porsche, whose fame is embodied in the legendary breed of sports cars carrying the same name) drove an Austro-Daimler of his own design to victory in the 1910 Prince Henry of Prussia Trial – on Riley wheels. In 1912, Fritz Erle, a famous German driver of those pioneering years, won the Gaillon Hill-Climb in France, making that his farewell drive as he retired immediately afterwards. But the Blitzen Benz wasn’t through yet. One such car won the 1914 Russian Grand Prix – a 150-mile race on mostly unmade roads – at a speed of more than 70 mph.

Riley wheels were fitted to the great Napier racers of the pre-WW1 period and to Renault sporting cars of the period, once detachable wheels became fashionable and widely accepted. Rolls-Royce fitted them to the Alpine Eagle which won the 1913 Alpine Trial and the American Pierce Arrow company fitted them to their fine touring cars. Down-market, they made a low-cost wheel for the Ford Motor Company and up-market, they made them for the mighty Hispano-Suiza, where cost was no object.

Illustration from 1912, (illustration 23)

Also from 1912 is Illustration 23. The original picture is very small and was used to fill the bottom of an "Autocar" column. On examination the 'lorry' appears to be a modified 12/18 h.p. car. If this is a 12/18, it is in company with the 9 h.p. V‑twin, flat‑bed, truck made to move the factory plant in 1906, and the various 9 h.p. vans described in the bulletin over the years.

The following is a little comment from David Styles on the published list of cars which used Riley wheels.

In that list there are some worthy tales to tell – of the 100hp Austin’s developed for the 1908 French Grand Prix, where the cars were banned from carrying spare wheels because competitors were not allowed to carry “spare parts”. The mighty Blitzen Benz cars were fitted with special wheels made by Riley and Victor Hemery set up a new speed record at Brooklands in 1909 of 127.4 mph. In America, the famous Barney Oldfield broke that record with 131.1 mph speed at Daytona Beach and in 1911, another American, Bob Burman then set a new world speed record of 141.7 mph, which stood until after the Great War.

Dr. Ferdinand Porsche (father of the present Dr. Ferry Porsche, whose fame is embodied in the legendary breed of sports cars carrying the same name) drove an Austro-Daimler of his own design to victory in the 1910 Prince Henry of Prussia Trial – on Riley wheels. In 1912, Fritz Erle, a famous German driver of those pioneering years, won the Gaillon Hill-Climb in France, making that his farewell drive as he retired immediately afterwards. But the Blitzen Benz wasn’t through yet. One such car won the 1914 Russian Grand Prix – a 150-mile race on mostly unmade roads – at a speed of more than 70 mph.

Riley wheels were fitted to the great Napier racers of the pre-WW1 period and to Renault sporting cars of the period, once detachable wheels became fashionable and widely accepted. Rolls-Royce fitted them to the Alpine Eagle which won the 1913 Alpine Trial and the American Pierce Arrow company fitted them to their fine touring cars. Down-market, they made a low-cost wheel for the Ford Motor Company and up-market, they made them for the mighty Hispano-Suiza, where cost was no object.

Illustration from 1912, (illustration 23)

Also from 1912 is Illustration 23. The original picture is very small and was used to fill the bottom of an "Autocar" column. On examination the 'lorry' appears to be a modified 12/18 h.p. car. If this is a 12/18, it is in company with the 9 h.p. V‑twin, flat‑bed, truck made to move the factory plant in 1906, and the various 9 h.p. vans described in the bulletin over the years.

Addendum - not in original publication

Riley produced a cheaper bolt-on version of the detachable wire wheels from 1913 season onwards. They look the same as the detachable ones, but without the detachable wheel mechanism. I would assume that the rear flange is flat (or partially flat near the holes) to cope with the nuts.

Riley produced a cheaper bolt-on version of the detachable wire wheels from 1913 season onwards. They look the same as the detachable ones, but without the detachable wheel mechanism. I would assume that the rear flange is flat (or partially flat near the holes) to cope with the nuts.